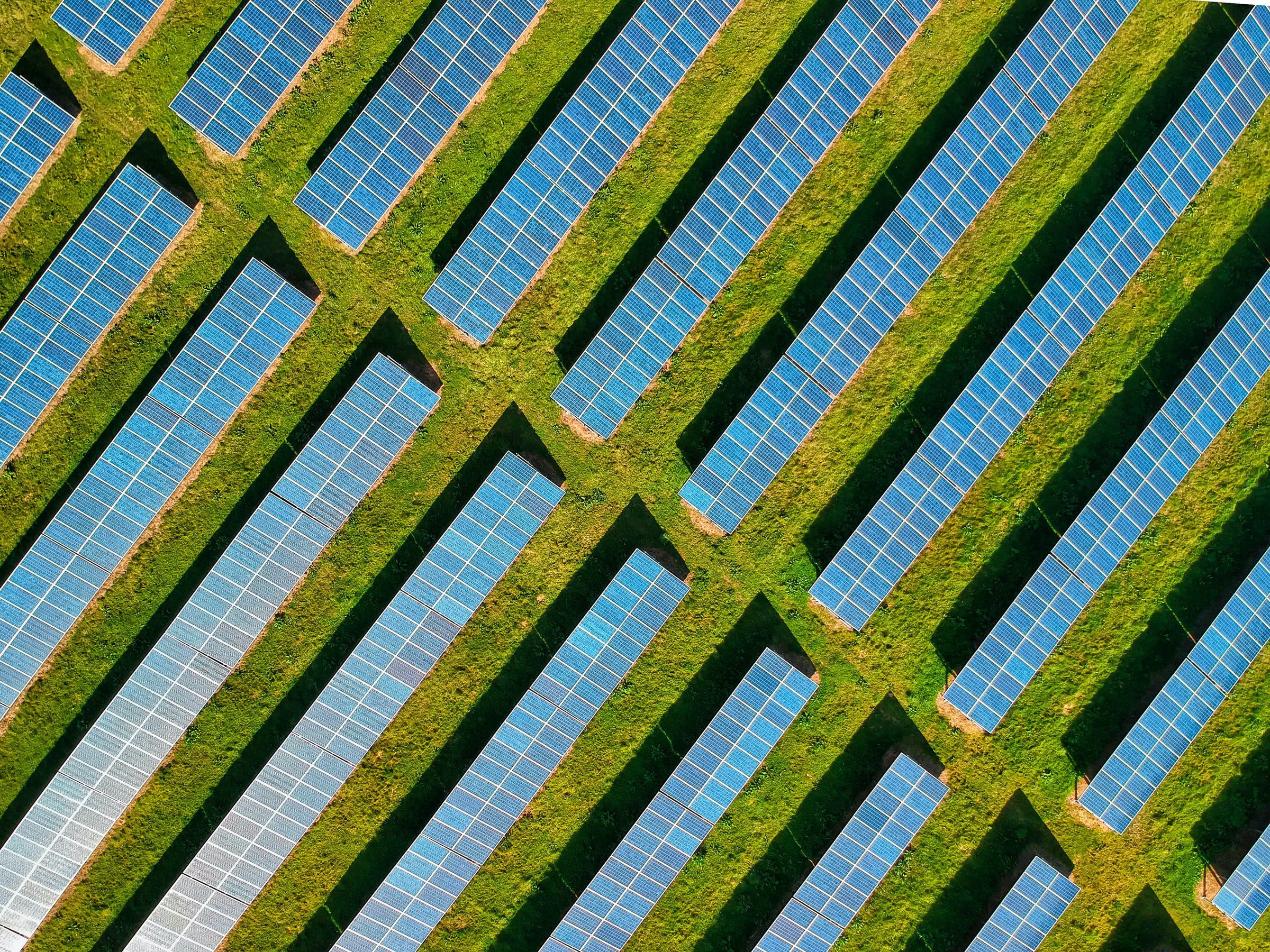

When you hear the term ‘solar farm,’ the first thing that comes to mind is an image of sprawling fields of metallic-looking panels with minimal vegetation in sight. While it is a farm for solar energy, most would assume that the only thing solar farms have in common with conventional agriculture farms is the name. A farmer in Colorado is determined to prove that blending the two concepts is not only possible but mutually beneficial – and he has the science to back it up.

A number of years ago, Byron Kominek, who had just wrapped up working with the Peace Corps and as a diplomat in Africa, returned to his family’s multi-generational farm outside of Boulder, Colorado. Upon his return, he learned that the business was in trouble.

The 24-acre plot had mostly produced hay for the last five decades. However, the farm had started to struggle with selling enough to turn a profit. To make matters worse, there were legal hurdles that prevented Kominek from transforming his family’s land into a more productive, non-agricultural business venture, as the land was designated as historic farmland.

Citing this designation, the regulators of Boulder County told Kominek that his plan of replacing his hay fields with solar panels wouldn’t be possible. “They said, land’s for farming, so go farm it,” said Kominek. He found this decision puzzling since he had been noticing a flurry of renewable energy initiatives popping up all over town. Surely such a sustainability-minded county would be ecstatic about a resident wanting to start their own solar farm. “I said, well, we weren’t making any money, you all want to be 100% renewable at some point so how about we work together and sort this out.”

What happened next was exactly that. The county eventually updated its land code, allowing Kominek to install the panels as long as he continued to farm the land underneath. It appeared at first that the underlying crop was going to be there purely for legal reasons, and Kominek would expect the vast majority of the farm’s profitability to come from the panels. After all, the panels were now crowding the plants as well as shading them at points throughout the day– all things that one would expect to lead to a disappointing harvest.

To everyone’s surprise, the opposite happened. Kominek soon discovered that a curious yet positive interaction would take place between the panels, the shade, and the underlying crop and irrigation water.

The panels would shade the crop at different intervals depending on the sun’s location, which in turn would lessen the evaporation of the irrigation water. With more water available, the crop and soil underneath would end up richer in nutrients. To complete the cycle, the water that continued to evaporate during sunnier stretches would then provide a cooling effect for the panels, which helps them harvest solar energy with increased efficiency.

The rebranded Jack’s Solar Garden, named after Kominek’s grandfather, is now one of only a dozen American farms that have made forays into the up-and-coming agrivoltaics industry. The days of hay farming have ended, but the success of the panels has allowed Kominek to plant a host of different crops including kale, tomatoes, peppers, squash, and much more. The farm is the largest of its kind in the country and is helping academics from the University of Arizona form models for lessening the impact of drought on farms within their state through water conservation. What was an enormous gamble just a few months earlier is now looking like it will pay dividends for years to come.