(Bloomberg) —

At the end of 2021, the US had 1,144 gigawatts of utility-scale electricity generation capacity. That includes everything from 130-year-old hydro dams to brand-new wind farms and solar projects with batteries attached. It took over a century to install all of it, and today, companies want to build almost that much capacity, all over again.

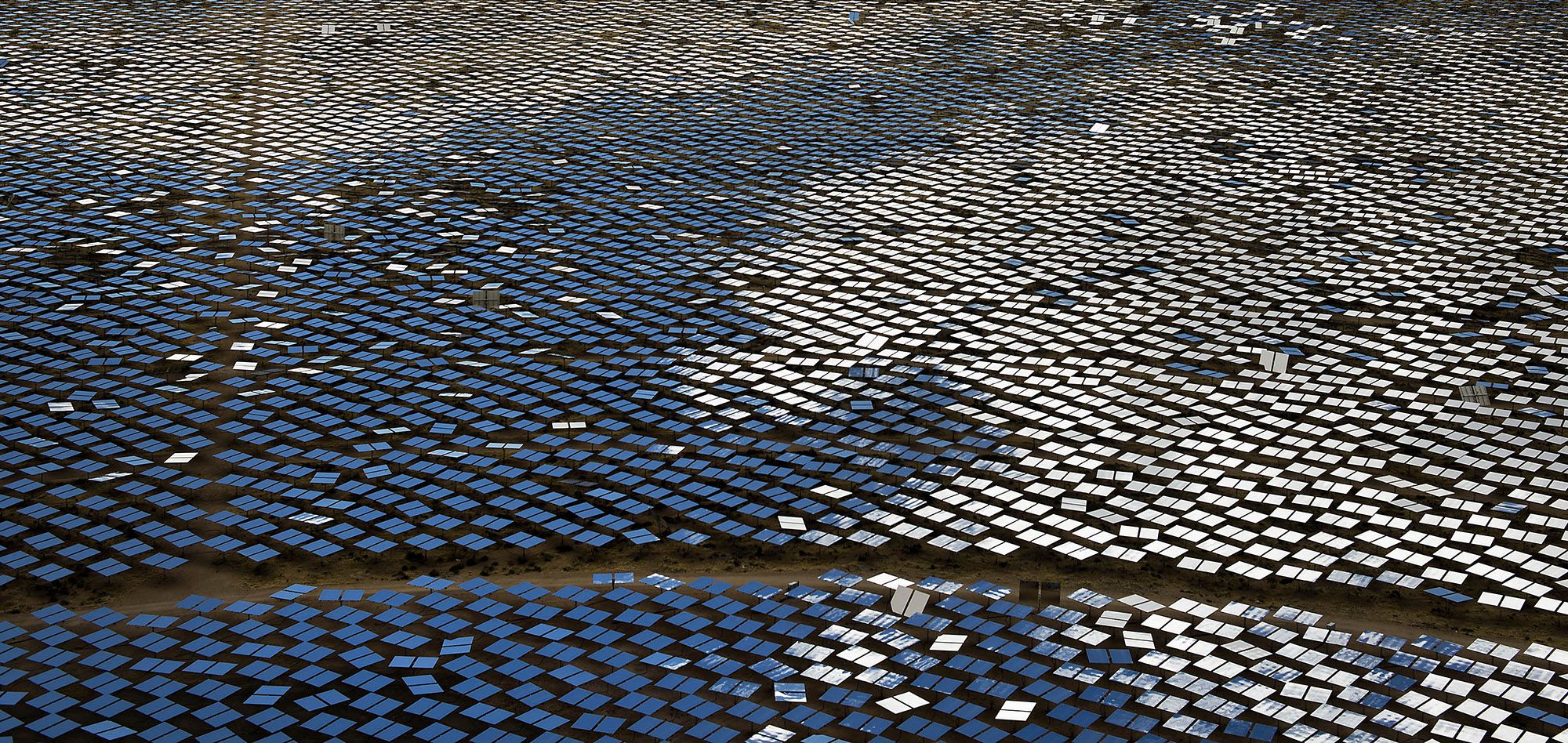

In its annual review of utility-scale solar, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory analyzed data from seven independent system operators and 35 utilities, which together represent about 85% of the nation’s electricity load, to see what’s awaiting connection. It found more than 1 terawatt of potential new power generation or storage capacity that has requested connection to transmission networks. To put that in perspective, the whole world hit 1 terawatt of installed solar capacity earlier this year.

The Berkeley Lab data tells the story of US solar power — from its growth to its technological sophistication to its growing maturity as a sector.

Firstly, most new power generation planned in the US is renewable. In 2014, the total of all resources in all combined interconnection queues was about 325 gigawatts, of which 14% was solar. Today, it is 1,450 gigawatts (including energy storage projects), 46% of which is solar.

Now an important qualification in the lab’s own words: “Not all of these projects will ultimately be built!” Even a massive expansion of continent-wide transmission would not create enough space for all of these assets to be connected to the grid. Nevertheless, the scale of ambition is important. Every asset in the queue represents dollars invested and time spent.

Secondly, solar project developers are clearly interested in batteries, though that interest varies greatly by region. More than 95% of solar capacity planned for California includes batteries. Storage is prevalent in the far West and in the sunny Southeast; less so in the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest. Still, with the exception of New York state and the Plains states, every major region plans to have batteries integrated with at least 20% of the solar in its interconnection queue.

In other words: In sunny markets where there is already a high penetration of renewable power generation, storage is more or less expected with a new solar project. It is not quite so automatic a decision in the southeast or Texas, but I would wager that it will be.

Underneath the raw capacity numbers, Berkeley Lab also observes some trends that show how the market is maturing and continuing to innovate.

One important trend is the movement of new projects to areas with less intense sun. Global horizontal irradiance (a technical way of measuring how much sun an area receives) peaked for US solar projects in 2013. This is not really a surprise. Project sites with the very best solar resources were snapped up years ago and many have already been developed. And as the market moves from high-irradiance sites such as the desert Southwest and California into the Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, Midwest and Northeast, solar intensity necessarily declines.

Yet at the same time, the amount of solar power generated by US projects has not significantly declined since its peak. The average capacity factor (a measure of how much energy is produced compared with maximum potential annual output) for projects that began operation in 2013 was 25.1%; in 2020, it was 24.8%.

The reasons for this (very good!) plateau are worth noting. The first is that today, nearly every large solar project includes tracking systems that follow the sun across the sky, increasing capacity factor.

The second is that project owners have increased their “inverter loading ratio” — basically, they build more capacity than specified for the hardware that turns the variable direct current of solar panels into the alternating current of the grid. This is a feature, not a bug, as it allows for more output and less variability.

Berkeley Lab’s annual review of solar is a useful stocktake of how far the industry has come in the past decade. Read it carefully, and it is also a glimpse of the future — and not just for solar. The one-word version of that look-ahead? Batteries. It’s not just the amount of battery capacity in interconnection queues that’s important, it is also the where and the why.

In California, 42% of wind capacity in the queue includes batteries — and in Texas, 27% of the gas-fired power does too. The continuing expansion of batteries’ scope is something to watch for in the next report.

Nat Bullard is a senior contributor to BloombergNEF and Bloomberg Green. He is a venture partner at Voyager, an early-stage climate technology investor.

To contact the author of this story:

Nathaniel Bullard in Washington at nbullard@bloomberg.net

© 2022 Bloomberg L.P.